Definitions of Mentoring

Understanding of the term ‘mentoring’ varies widely and is often used interchangeably with the word ‘coaching’. It is important to start by giving a definition of what is meant by mentoring in the context of what is being attempted. The following are some examples of definitions of mentoring from a variety of organisations and some of the classic generic definitions:

Models of Mentoring

The Focus Group started with this issue of defining mentoring. It is equally important to ensure that there is a common understanding as to whether the scheme is intended to focus on career sponsorship, or whether it has a greater emphasis on learning and development, which is the model found more commonly elsewhere.

The Henley Focus Group Model of Mentoring

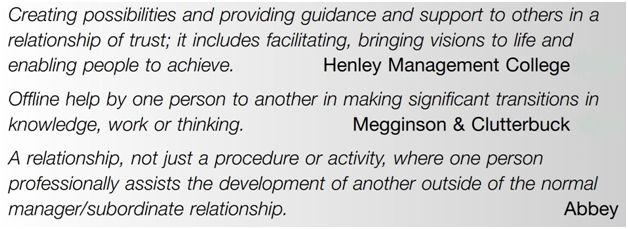

After a review of the various schemes represented in the Group at the time, the Henley Focus Group Model of Mentoring was developed (see Figure 1.1). This represented all the main categories of mentoring schemes which were familiar to organisational scheme managers. It also allowed for progression from one type of scheme to another, as a programme matured or the organisational requirements changed. In addition, it was found that in some organisations, several different types of scheme were operating simultaneously – and perfectly effectively. The differences occurred due to the explicit purposes of the schemes, and as long as there was agreement about this, each type of scheme had an equally good chance of success.

The Henley Focus Group Model (Figure 1.1) is useful as it allows for a broad-brush categorisation of schemes, each with their own organisational issues to manage. Once it is clear which type of scheme best meets a particular organisational requirement, it is much simpler to begin to map out the implementation process required to make it work.

Figure 1.1 The Henley Focus Group Model of Mentoring

The model is based around two axes, one of which looks at whether the mentoring scheme is structured or unstructured, and the other looks at whether the scheme is formal or informal. The four categories highlighted in the matrix may be understood from the following characteristics:

- Embedded: These are the formal, structured, schemes found in organisations such as the ones in the Focus Group. Such schemes are linked to the organisation’s development strategies and/or performance management processes. They will have specific, stated objectives, often targeted at specific groups such as graduates or high flyers and usually run for a defined timeframe of, say, 12 or 24 months.

- Ad hoc: These schemes frequently follow on from successful embedded schemes. Ad hoc programmes are official but uncontrolled, that is, started by the organisation, but left to run pretty much by themselves. Databases of mentors, which can be accessed via an intranet/internet site, allow for self-selection by mentors according to their needs.

- Social: Both informal and unstructured, this type of mentoring is driven by the learner and goes largely unrecognised as being ‘mentoring’. Prefaced by phrases such as ‘Can you help me with …’, learners approach colleagues or friends for help with a problem. It occurs on a haphazard, needs-driven basis.

- Self-help: This is a more structured method of informal mentoring, where the learner recognises a specific development need and requests help from an ‘expert’. This can also move over into the coaching category and away from a true mentoring relationship. While there are some ground rules set around the relationship, such as more regular meetings, it retains a more social style.

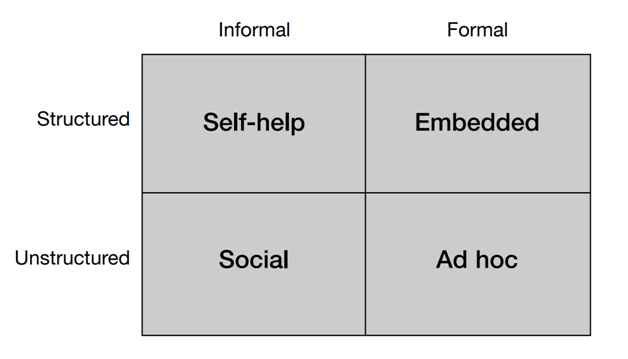

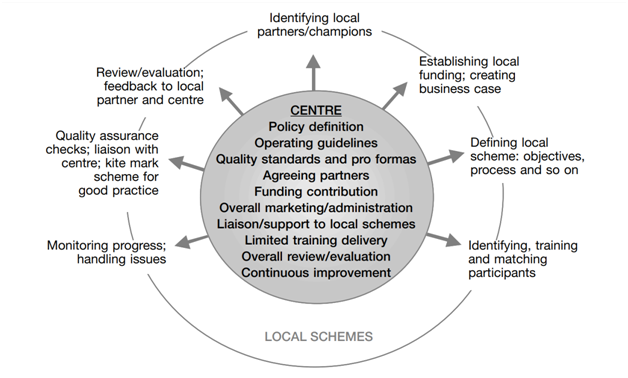

A Centralised Mentoring Model

This is where all activities to do with the mentoring scheme are developed and handled by a central department, usually HR or training and development. This was the approach most commonly used by organisations in the Focus Group. The main advantage of using a centralised model is that decision-making is relatively quick and, usually, rests with the scheme manager. The risk is that the resource level required to manage the scheme on a day-to-day basis is often insufficient. In many of the Focus Group organisations, mentoring was only one of many responsibilities carried by the scheme managers, and they found it challenging to devote sufficient time to keep on top of events.

Figure 1.2 A Centralised Model of Mentoring

A Decentralised Mentoring Model

This is a less commonly seen model for mentoring (Figure 1.3), where key policy decisions on minimum standards and guidance are made centrally, but the implementation of the mentoring scheme is the responsibility of a local group or organisation. It may be that this model suits the organisation from the outset, as with The Prince’s Trust; alternatively, it may be one that is adopted once the concept of mentoring has been successfully introduced and the scheme begins to grow.

Figure 1.3 A Model of Decentralised Mentoring

Decentralised mentoring allows interpretation of common frameworks and guidelines to suit local circumstances. Once principles have been agreed, funding arrangements made and a partner (or partners) found, the implementation and decision-making is the responsibility of the local partnership. Through quality checks and evaluation systems, the centre is able to keep an overall view of all the local schemes that are operating.

The Context for Action

In addition to the different methods of operating a mentoring scheme, there are, of course, many different reasons for introducing a scheme into an organisation. It can be aimed at developing specific groups of people or set up to support the overall strategic direction of the organisation in a wider sense. Ensuring that there is a clear context for the proposed scheme is all-important: it refines the broad-brush definition and makes it real for the people who will be involved in it.

Cross-Company Mentoring

Another ‘alternative’ approach to mentoring that was discussed was cross-company mentoring. This usually involves a reciprocal arrangement whereby managers from one organisation set up mentoring relationships with managers in another, instead of mentors and mentees both being from the same organisation. Unlike peer mentoring, cross-company mentoring seems to require a significant level of formality to be taken seriously but can be run either in an embedded way or on an ad hoc basis.

Group Mentoring

Another venture into alternative ways in which to set up a mentoring scheme is the idea of group mentoring. This can be useful where, as in the above two examples, the supply of mentors is a problem. Group mentoring can also be the ‘scheme of choice’ when there is an appropriate group of potential mentees who would benefit from the same kind of mentoring from the same mentor. This would be particularly likely with members of the same work team, for example, and where there was a specific objective as an outcome for the mentoring.

Global Mentoring Schemes

The challenges facing a global mentoring scheme are many: the first, but not always the most obvious, issue to consider is the difference in culture and business practice. The assistance that participants from different cultures will need when embarking on their relationship needs careful consideration. There are also the difficulties of physical distance and the inability to meet face to face.

Whilst some of these difficulties can be overcome by the use of e-mentoring methods, participants often find that distance and time zone differences can make the formation of a successful relationship extremely challenging. Careful forethought and planning will help to get a global mentoring scheme off to a good start. However, what plays a key role in its success is the ability of the scheme manager or local champions to keep in touch with the mentee and/or mentor, providing them with active support and encouragement.

Regular communication from a support team also keeps them informed about progress and alerts them to potential issues.

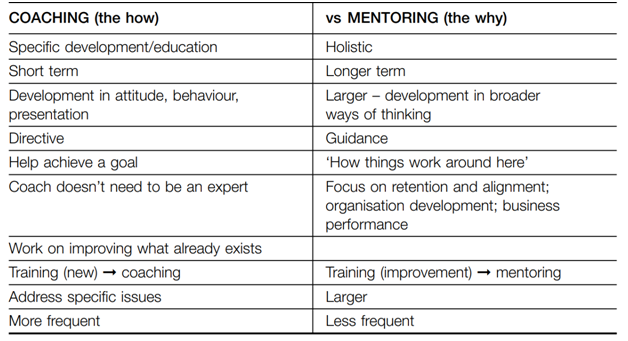

The Differences between Mentoring and Coaching

In the Mentoring Focus Group, this subject came up for discussion on several occasions, and it is a question that all scheme managers seem to have to answer whenever the subject of mentoring is raised for the first time. The need for clarification of the difference between mentoring and coaching has increased over recent times. It is noticeable that, in the early days of the Focus Group, ‘executive coaching’ was still a minority activity, with only a few individuals in an organisation receiving it for development purposes.

Coaching was likely to be seen as a remedial activity, whereas mentoring was much more acceptable as a positive, developmental intervention. Coaching is now a great deal more aspirational, for a much wider range of managers. This means that the merging of coaching and mentoring in people’s minds is more apparent now than it was previously. It is helpful, therefore, to have clear definitions for both activities and build this into any briefing activity.

In general terms, the Henley perspective is in line with the many textbook definitions of mentoring and coaching. Coaching is seen to be more skills-related, with specific, capabilities-linked outcomes. It would be perfectly acceptable, in many situations, for a line manager to coach a member of his or her staff and is often an expected role. Indeed, at Avaya, employees refer to their line manager as their ‘coach’.

Mentoring is positioned much more around the whole person and the big picture, and it is generally held that the line manager would not be appropriate as a subordinate’s mentor. This is mainly because the line manager has a performance management responsibility, which could get in the way of genuine mentoring conversations.

The quick differentiation seems to be that the mentoring relationship is where a person would be encouraged to explore areas in which they feel they might need some coaching.

During a Focus Group meeting specifically devoted to discussing the difference between coaching and mentoring, it was felt that there was a clear disparity in perceptions of status between being able to say ‘I am a coach’ and ‘I am a mentor’ and that this was more marked amongst senior management.

Table 1.3 Differences between coaching and mentoring as seen by the Focus Group

The Principles of Mentoring

Our work as mentors is to translate these very basic (and perhaps puzzling) philosophical positions into specific educational principles, which in turn govern our academic practices.

In brief, the following are the principles constituting Socratic dialogue in a contemporary academic setting.

- Authority and uncertainty: Act so that what you believe you know is only provisionally true.

- Diversity of curriculum: People learn best when they learn what draws their curiosity.

- Autonomy and collaboration: Treat all learning projects, all studies, as occasions for dialogue rather than as transmissions of knowledge from expert to novice.

- Learning from the “lifeworld”: Treat all participants to an inquiry as whole persons – that is, as people who hope to experience even in their busiest and most instrumental activities, the virtues and happiness which are ends-in-themselves, and give life meaning and purpose.

- Evaluation as reflective learning: Judge the quality of learning in the movement of the dialogue; expect that the content of individual outcomes will be, like all knowledge claims, incomplete and diverse.

- Individual learning and the knowledge most worth having: Honor and engage each student’s individual desire to know, and every student will learn what is important.

We will explain these principles more fully in our upcoming modules.

-

Add a note